Most Christians or Jews these days refer to the deity they worship simply as ‘God’, but he does have a name – Yahweh. This name appears over 6800 times in the Old Testament, and is generally translated as ‘the LORD’ in English translations of the Bible. This disguises the name Yahweh, and is no different from translating The Odyssey and replacing the name Zeus with GOD or the LORD every time it appears. I say the god of the Bible’s name is Yahweh, but that is technically only an educated guess. Hebrew has no vowels, and the name of the Jewish and Christian god is actually the Hebrew equivalent of YHWH.

By around the third century BCE, Jews decided that their god’s name was so sacred it should never be spoken and was replaced by the phrase ‘adonai’ (lord) when spoken or read. The Book of Leviticus goes so far as to state that ‘whoever utters the name of Yahweh shall be put to death’ (Leviticus 24.16). The name Yahweh does appear once in the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri, where the Jewish god’s name is often written as Iao or Iao Sabaoth.

The name Yahweh was then translated as kurios (lord) in the Greek version of the Jewish Bible, the Septuagint. This same translation as ‘lord’ continued in Latin and later language versions. Yahweh is believed to be the most likely pronunciation, based on Christian and Greek translations of the god’s name from antiquity. Medieval Christians translated the god’s name as Jehovah, and that name appears in older versions of the Bible, as well as in the name of the Christian sect ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses’. Whenever I quote the Old Testament on this website, I will translate the name of the god YHWH as Yahweh, not ‘the LORD’.

Other important earlier gods of the ancient Near East, were also referred to as ‘Lord’. The chief sky god of Sumerian religion was Enlil, his name literally means ‘Lord Wind.’ A Sumerian temple hymn refers to him as, ‘The great prince Enlil, the good lord, the lord of the limits of heaven, the lord who determines destiny, the Great Mountain Enlil’ (Temple Hymn 34-6). Hadad was a Mesopotamian and Canaanite sky and storm god, who was often called Baal (meaning Lord). Marduk, the chief god of Babylon, also came to be called by the name ‘Bel’, meaning ‘Lord’.

Yahweh wasn’t the only god worshipped by the ancient Israelites. We know that they also worshipped the gods El and Baal and the goddess Asherah, as well as possibly others. Israelite inscriptions discovered from the monarchy onwards include 557 names with Yahweh as the divine element, 77 with El and a handful with Baal.

El was the chief Canaanite god, and he may originally have been the main deity of the Israelites too. The very name Isra-El contains the name of the god El, and Israel is an old name, known from Egypt, Ugarit and Ebla. El is also the generic word for ‘god’ in western Semitic languages such as Hebrew and Aramaic. This also suggests that El was the chief deity in the early Israelite pantheon, as his name literally meant ‘God’. The word el appears 230 times in the Bible, and it’s used as a proper name for the god of the Bible in Psalms, Job and Isaiah.

In the Bible, Yahweh absorbed many features of the earlier Canaanite deity El. El is notably the only other Israelite god that the writers of the Bible didn’t try to denigrate. El was known by the epithets ‘the Bull’ and ‘the King’. El was also described in the Baal Cycle as ‘the Creator of Creatures’, a role Yahweh later went on to fulfil in the Bible. The other gods of the Canaanite pantheon were called ‘the circle of El’, ‘the assembly of the stars’ and ‘the circle of the throne of heaven’. El was depicted as sitting at the centre of this heavenly circular assembly, sometimes upon his holy mountain Lel. Yahweh was similarly depicted in the Bible,

‘God takes his stand in the assembly of the gods. He gives judgement in the middle of the gods.’ (Psalms 82.1)

In ancient Greece, the Homeric Hymns similarly mention a ‘council of the gods’ and ‘an assembly on snowy Olympus’ (e.g. Homeric Hymn 4 to Hermes 325 – 330). The Odyssey similarly states, ‘the gods sat down in council, circling Zeus who thunders on high.’ (The Odyssey 5.3-4). We find the same description in The Iliad, ‘Zeus the thunderer made an assembly of all the gods upon the highest peak of rugged Olympus’ (The Iliad 8.1). We also find this motif in Mesopotamian religion.

In Sumerian religion, the sky god An also sat on his celestial throne with the divine council of gods around him. He was described in a hymn as being, ‘imbued with awesomeness on the mountain of pure divine powers, who has taken his seat on the great throne-dais, An, the king of the gods…He has made all the great divine powers manifest, the gods of heaven stand around him.’

In the Canaanite city of Shechem, the local god was El Berit – ‘El of the covenant’. The idea of a covenant between Yahweh and the people of Israel, and in particular their kings, became central to the Old Testament narrative. There was also a tradition of El’s home as a tent in the Ugaritic texts, and the tent or tabernacle became Yahweh’s abode in the Bible.

El was depicted by the Canaanites in both texts and iconography as a bearded old man sat on a throne, the same imagery was later used to depict Yahweh. Just like Yahweh, El was considered the creator of the world, and was also called the ‘ageless one’ and ‘father of years’. In the Bible, Yahweh’s throne is placed in the sky, ‘I saw Yahweh sitting on his throne with all the host of heaven standing on his right and left’ (2 Chronicles 18.18), ‘Yahweh has established his throne in the heavens’ (Psalm 103.19).The Book of Daniel uses similar phrase ‘Ancient of Days’ to describe the Jewish god.

Evidence from the Bible itself also may suggest that the Israelites originally worshipped El, but he was later absorbed into the new chief god Yahweh. We read in the Book of Exodus,

‘And God said to Moses, “I am Yahweh. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, as El Shaddai, but I didn’t make myself known to them by my name Yahweh.” (Exodus 6.2-3)

A similar thing happened in Canaanite religion at Ugarit. El was originally the chief god there, but he was replaced at a later date by Baal. El was also known as the ‘Most High’, and this became an epithet of Yahweh in the Bible – El Elyon – ‘the most high god’. We also find something similar in Sumerian religion. The original chief god there was An (whose name literally means ‘sky / heaven’), who was seen as the father of the gods. However, he barely features in Mesopotamian art, and was replaced by Enlil, a sky god, as the chief god.

The Old Testament regularly describes Yahweh as a sky and storm god similar to Baal Hadad and Zeus. Genesis states that he is, ‘Yahweh, the god of the sky [heaven]’ (Genesis 24.7). The book of Job states of the biblical god, ‘Who can understand how he spreads out the clouds, how he thunders from his pavilion?’ (Job 36.29). It follows this with, ‘He fills his hands with thunderbolts and launches them to strike the target. His thunder heralds the coming storm’ (Job 36.32-33). The Psalms also depict Yahweh as a storm god,

‘Yahweh thundered from the sky

the voice of the most high rang out.

He shot his arrows and scattered them,

with many lightening bolts he frightened them.’ (Psalms 18.13-15)

We find the same imagery of a thundering storm god used by the authors of the books of Jeremiah, Joel and Amos. The Canaanite Ugaritic texts predate the Bible, and they often give Baal the title, ‘Rider on the Clouds’, and describe him sending lightening down to earth, with thunder being his voice (Baal Cycle II AB iv 70-1).

Yahweh, Zeus and Baal also all rule from a holy mountain, probably representing the north celestial pole. In Baal’s case the mountain is mount Zaphon, which literally means ‘the mountain of the far north’. In Yahweh’s case it’s Mount Zion, while Zeus’ home is Mount Olympus. Baal was also known as ‘the Most High’ in the Ugaritic texts, and fought a celestial dragon called Litan, which became Leviathan in the Bible. Zeus likewise fought Typhon. Language derived from the Canaanite worship of Baal and El also appear in the Bible, such as in Isaiah,

‘I will raise my throne

above the stars of El (God).

I will sit enthroned on the Mountain of Assembly,

on the northernmost heights of Mount Zaphon.

I will ascend above the tops of the clouds,

I will make myself like the Most High (El-yon).’ (Isaiah 14.13-14)

The Mesopotamian storm god Tishpak was another similar deity. He was both a storm god and a warrior god, who was titled ‘lord of the armies’, just like Yahweh. He was also linked to a snake-dragon. The Hurrian / Hittite god Teshub is another sky and storm god from the ancient Near East with a similar mythology to Yahweh and Baal. One of his main stories was his battle with the dragon Illuyanka, and he was also a warrior god known as ‘the lord of hosts’ and ‘king of heaven’. The Sumerians worshipped a similar storm god called Ishkur. Enki and the World Order describes him as, ‘He who rides on the great storms, who attacks with lightning bolts’ (Enki and the World Order 312-13). In Vedic Indian religion, Indra is another similar deity.

Baal and Yahweh both have numerous similarities to the chief Greek god Zeus and his Roman counterpart Jupiter. Zeus ruled the sky from his holy mountain Olympus, and was also usually depicted in art and described in literature as wielding a thunderbolt.

The Homeric Hymns date to around the 7th – 6th centuries BCE. They describe the king of the gods as ‘Zeus the loud-thunderer’, ‘Zeus the thunder-lover’, and ‘cloud-gathering Zeus’. The Iliad dates from a similar time and it describes Zeus as ‘Zeus who thunders on high’, ‘Zeus, the cloud-gatherer’, ‘Zeus that throws the thunderbolt’, ‘father Zeus, throned on high’ and ‘Zeus most high’.

Hesiod’s writings also date to around the same time (late 8th century), and he called Zeus, ‘the Thunderer whose home is high’ (Works and Days 9). Zeus was also linked to bull imagery, in the myth of Europa he transformed into one. The Orphic Hymns describe Zeus in a very similar fashion to the biblical depiction of Yahweh. He’s a sky and storm god who controls the cosmos,

‘Father Zeus, sublime is the course of the blazing cosmos you drive on, ethereal and lofty the flash of your lightning as you shake the seat of the gods with a god’s thunderbolts. The fire of your lightning emblazons the rain clouds, you bring storms and hurricanes, you bring mighty gales, you hurl roaring thunder, a shower of arrows. Horrific might and strength sets all aflame.’ (OH 19.1-7)

As well as being a sky / storm god, Yahweh is also described as a warrior god. There’s plenty of evidence for his belligerent nature in the Bible in passages like,

‘This is the day of the lord Yahweh of the armies.

A day of vengeance, for vengeance on his enemies.

The sword will devour until it is sated,

until it is drunk with their blood.

There will be a slaughter for the lord Yahweh of the armies

In the north land by the river Euphrates’. (Jeremiah 46.10)

Yahweh’s warrior nature is clearly spelled out in the Book of Exodus where we are told, ‘Yahweh is a warrior, Yahweh is his name’ (Exodus 15.3). The god is similarly described in Isaiah,

‘Yahweh will go forth as a warrior,

he will rouse his fury like a man of war.

He will shout out his battle cry

and triumph over his enemies.’ (Isaiah 42.13)

He is also called ‘Yahweh of the armies’ (Yahweh sabaoth) 287 times in the Old Testament, but this is translated as ‘the LORD of the hosts’ or ‘the LORD almighty’ in most English translations, covering up Yahweh’s bellicose nature. These armies were probably believed to be celestial in nature. Numbers 21.14 also mentions a now lost piece of Israelite scripture called ‘The Book of the Wars of Yahweh’. In Judges, We are told that he routs the army of a Canaanite commander called Sisera by setting the stars themselves on Sisera!

‘From the heavens the stars fought,

from their courses they fought against Sisera.’ (Judges 5.20)

Many deities of the ancient Near East were depicted as powerful warriors, mirroring the image the kings wanted to project of themselves. Unfortunately, warfare was commonplace in the Bronze and Iron Age. In ancient Sumer, the deities Inanna, Nergal and Ninurta were all warrior deities. Assyria was the main powerhouse of the region during the existence of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Its all conquering army was known as the ‘hosts of the god Assur’.

Yahweh was also the royal god of the kings of Judah. These kings were the ‘anointed’ of Yahweh (technically the original ‘messiahs’). This royal theology was common in the ancient Near East. In the Babylonian and Assyrian empires, the chief gods Marduk and Ashur were linked to the king. In Egypt, Horus was the original royal patron deity, although later Amun took that role, and pharaohs were also considered to be sons of the solar god Re. Ancient Near Eastern kings were often depicted as sons of a major god. In the Bible, the Psalms describe the king of Judah as Yahweh’s son (Psalm 2.7-12).

Yahweh wasn’t originally the universal ‘God’ modern Christians and Jews believe him to be. He was originally a storm / sky / warrior god who became the patron god of the royal family of the two small Iron Age kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

The god of the Old Testament is depicted as a most unpleasant figure – angry, vengeful and violent. Isaiah states of him,

‘I will make your enemies eat their own flesh.

They will be drunk on their own blood, as with wine.’ (Isaiah 49.26)

and,

‘I will trample the nations in my anger,

and make them drunk in my fury,

and pour their blood on the ground.’ (Isaiah 63.6)

In the book of Ezekiel, Yahweh turns this vicious streak on his own worshippers in Judah,

‘Therefore, says the lord Yahweh, I myself will be against you. I will inflict punishment on you for the nations to see. Because of your abominable practices I will inflict such punishments as I have never executed before nor ever will again. Therefore Jerusalem, parents will eat their children and children their parents in your midst.’ (Ezekiel 5.8-10)

Nahum likewise states of the deity, ‘Yahweh is a jealous and vengeful god. Yahweh takes vengeance and is filled with wrath’ (Nahum 1.2). Yahweh shows his violent streak throughout the Old Testament. In the Book of Numbers he kills almost 15,000 of his own people for merely questioning the authority of Moses (Numbers 16.32-50).

The two major differences between the worship of Yahweh in the Bible and that of other deities of the time are a noticeable intolerance towards the worship of other gods, and the opposition to idolatry and depicting gods in human form. This was a fairly late development in Israelite religion though, the texts denouncing idolatry are usually from the Deuteronomist or Priestly sources and most probably date from the Babylonian exile or even later.

In the earlier parts of the Bible, Yahweh is openly depicted in anthropomorphic terms, which suggests there wasn’t always this opposition to depicting gods in human form. In the Book of Genesis, Yahweh walks in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3.8), he also talks to Cain, Noah, Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 4, 6, 12 and 26). He also smells ‘the pleasing aroma’ of sacrifices that Noah makes to him (Genesis 8.20-21), and even wrestles with Jacob! (Genesis 32.22-32).

We are of course also told that ‘God created man in his image’ (Genesis 1.27), which implies that Yahweh was seen as having human form. The evidence also suggests that he may also originally have had a consort, the goddess Asherah. His worship may have become aniconic under Persian rule, Herodotus wrote that Persian religion wasn’t anthropomorphic like Greek religion.

The first century Jew Philo noted the anthropomorphism of Yahweh present in the Old Testament when he wrote,

‘Why, then, does Moses speak of the uncreated as having feet and hands, and as coming in and as going out? And why does he speak of him as clothed in armour for the purpose of repelling his enemies? For he does speak of him as girding himself with a sword, and as using arrows, and winds, and destructive fire. And the poets say that the whirlwind and the thunderbolt, mentioning them under other names, are the weapons of the cause of all things. Moreover, speaking of him as they would of men, they add jealousy, anger, passion, and other feelings like these.’ (On the Unchangeableness of God XIII.(60))

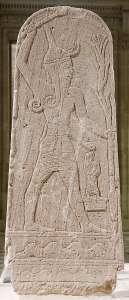

If we want to imagine how the Israelites may have originally viewed Yahweh, we should probably look at depictions of similar gods, like El, Enlil, Hadad, Baal and Zeus. These gods were either depicted as a king sat on his heavenly throne or as a smiting god, often carrying a thunderbolt.