There’s a long and ancient tradition of religious belief in the world axis as a conduit between the sky and the earth, and the polar region of the sky as being a gateway to the divine realm. This belief goes back at least 4500 years, probably even longer. The ancient Egyptians believed that the soul of a deceased king ascended to the polar region of the sky after death. The Egyptians called the circumpolar stars ‘the Imperishable Stars’ because they never set. In his introduction to The Egyptian Book of the Dead, R. Faulkner wrote,

‘The Egyptians could believe in an afterlife in which the deceased would spend eternity in the company of the circumpolar stars as an akh.’

These immortal stars were a logical place for the soul to travel to after death to ensure its own immortality. The deceased soul would then become part of the whole celestial order. The Pyramid Texts describe the relationship between the dead king and these stars,

‘I am back to back with those gods in the north of the sky, the Imperishable Stars; therefore I will not perish – the Inexhaustibles – therefore I will not become exhausted’ (Utterance 503).

In utterance 302 of The Pyramid Texts, the asterism of the Big Dipper is specifically given the title ‘the Imperishable’. Utterance 269 describes the dead pharaoh’s ascent to the circumpolar stars,

‘Here comes the ascender, here comes the ascender!

Here comes the climber, here comes the climber!…

…My father Atum seizes my hand for me,

And he assigns me to those excellent and wise gods,

The Imperishable Stars.’

Utterance 480 of the Pyramid Texts tells of the dead king ascending a ladder to the Imperishable Stars. Utterance 513 states that the dead king ‘ascends to the sky among the gods who are in the sky. He stands at the Great Polar Region.’ Utterance 667 reads, ‘A stairway to the sky is [set up] for you among the Imperishable Stars.’

Utterance 509 mentions the dead king sitting on an iron throne among the Imperishable stars. This passage reads, ‘I ascend to the sky, I cross over the iron [firmament]… I ascend to the sky among the Imperishable Stars, my sister is Sothis [Sirius], my guide is the Morning Star…I sit on this iron throne of mine.’ Another utterance states of the dead king, ‘My bones are iron and my limbs are the Imperishable Stars’ (Utterance 570).

The Coffin Texts also mention this, ‘You shall sit on the iron throne, you…shall rule the Imperishable Stars’ (spell 517). Numerous ancient cultures thought the celestial sky dome was made of iron / metal. This might be due to iron rich meteorites that had fallen from the sky and were seen as originating from the realm of the gods.

The soul of the deceased king was released from the mummified body to ascend to the heavens in a ritual called the opening of the mouth ceremony. This rite involved the mummy being struck with an implement called the adze of Wepwawet (a canid headed god whose name means ‘the opener of the ways’). The Pyramid Texts state that, ‘Wepwawet has caused me to fly up to the sky among my brethren the gods’ (Utterance 302).

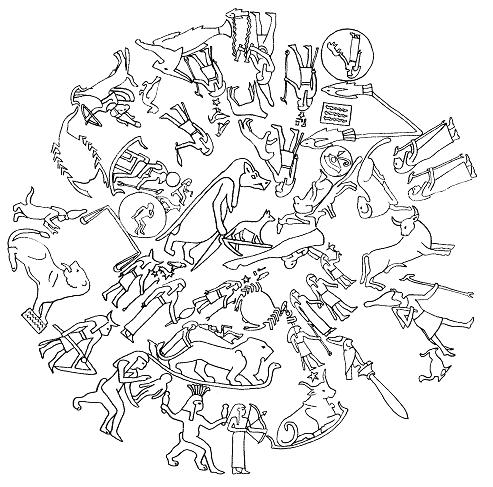

The Dendera zodiac depicts a canid at its centre, suggesting a link between Wepwawet and the celestial pole. The Pyramid Texts may also suggest this connection. They state of the dead king, ‘You shall ascend to the sky, you shall become Wepwawet’ (Utterance 482).

The tools involved in the Opening of the Mouth ceremony were also probably made of meteoric iron. The Pyramid Texts recounts this ritual, ‘[O King, I open your mouth for you] with the adze of Wepwawet, [I split open your mouth for you] with the adze of iron which splits open the mouths of the gods’ (Utterance 21).

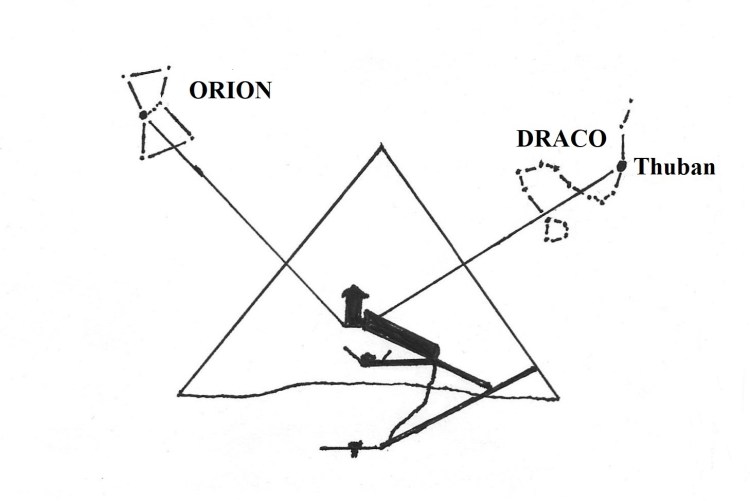

Tutankhamun was buried with a dagger made of meteoric iron, as well as meteoric iron blades and chisels that may have been used in his Opening of the Mouth ceremony. The star Thuban in the constellation Draco was the pole star at the time of the construction of the pyramids of Giza, and a shaft in the pyramid at Khufu pointed at this star. Interestingly, an Arabic name for this star is Adib – the wolf.

This canid connection to the celestial pole may have spread into other religions. In Persian mythology, there’s a being called Chamosh, described as having the body of a dog or wolf with the head and wings of an eagle. Chamosh lives upon the summit of the holy mountain Alborz, and inhabits the ground beneath the soma tree. One of the ancient Greek names for the constellation of Ursa Minor was Cynosura, which means ‘the dog’s tail’. An otherwise strange name for a bear constellation. Indeed both circumpolar bear constellations are peculiar in having long tails that bears don’t actually possess.

The connection may also be the origin of Cerberus, the canid guardian of the Hades. Cerberus was the offspring of the serpentine Typhon and Echidna, and had a mane of snakes. Pseudo-Apollodorus wrote, ‘Cerberus had three dog-heads, a serpent for a tail, and along his back the heads of all kinds of snakes’ (Bibliotheca 2. 122). He was also often described as being chained up, just like the bear constellation Ursa Major, which was seen as being chained to the pole.

If the axis was the route to the afterlife, it could also have been the way to the underworld. Anubis was the canid headed dog linked to the afterlife in Egyptian religion. There might also be a link to Fenrir, the giant wolf of Norse mythology, who was chained up by the gods. This canid may also appear in Norse mythology as Garm, the dog who guarded the entrance to the underworld.

The same belief in the ascent of the pharaoh’s soul underpins the construction of the Egyptian pyramids. Passages pointing at the pole star were a common design feature of most pyramids. These passages ran from the main chamber to the outside of the pyramid, and were there to allow the pharaoh’s soul to ascend to the stars.

The burial chamber of the pyramid at Meidum was entered by a passage that pointed at the celestial pole. The tomb chambers of the Bent and Red pyramids of Dahshur were also entered by passages pointing at the northern pole. Shepseskaf, the last of the Fourth Dynasty pharaohs, broke with tradition by building a mastaba tomb rather than a pyramid. His burial chamber was once again reached by a passage pointing to the celestial pole.

In the Great Pyramid of Khufu, two narrow shafts exited the King’s Chamber. The northern one pointed at the star Thuban in the constellation Draco, the pole star at the time. The southern shaft pointed at Orion’s belt. Orion is consistently mentioned by The Pyramid Texts as a constellation linked to the celestial rebirth of the Pharaoh, along with the circumpolar Imperishable Stars, Sirius (called Sothis by the Egyptians), the Morning Star (the planet Venus) and Re (the Sun).

The later Coffin Texts also linked these specific stars to the rebirth of the deceased, ‘It is Orion who has given me his warrant, it is the Great Bear which has made a path to me to the western horizon, it is Sothis who greets me as the birth of a god’ (spell 482).

Plato’s The Republic gives us a fascinating ancient Greek example of the belief in the journey of souls between the earth and the heavenly realm after death, in a section called The Myth of Er,

‘The souls rose up again and came on the fourth day to a place from which they could see a shaft of light running straight through heaven and earth, like a pillar, in colour most nearly resembling a rainbow, only brighter and clearer. After a few days journey they entered this light and could then look down its axis and see the ends of it suspended from heaven, to which they were tied. This light is the tie-rod of heaven which holds its whole circumference together like the braces of a trireme, holding together in like manner the entire revolving vault. And to these ends is fastened the spindle of Necessity, which causes all the orbits to revolve’ (The Republic 10.616).

The transmigrating souls enter a pillar of chromatic colours that could represent the cosmic axis.

It’s interesting that Plato described this shaft as ‘a pillar, in colour most nearly representing a rainbow’. In Norse mythology, the Bilfrost bridge was a rainbow bridge that divided the heavenly realm of the gods (Asgard) from the earth (Midgard), which has been equated to the world axis. In the Bible, a rainbow was also the sign of the covenant after the flood in the Old Testament.

A Sumerian text called Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird speaks of a tree on a multicoloured mountain that again suggests the world axis, ‘The splendid eagle-tree of Enki on the summit of Inana’s mountain of multi-coloured cornelian stood fast on the earth like a tower…with its shade it covered the highest eminences of the mountains like a cloak’ (Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird 28-32).

In Islamic mythology, Muhammad encountered a giant lote tree called Sidrah Al-Muntaha in his ascent through the seven heavens. This celestial tree is described as being shrouded in indescribable colours (Sahih al-Bukhari 3342). In Greek mythology, the goddess Iris was the goddess of the rainbow and the messenger of the gods, again suggesting the belief in a rainbow as a link between heaven and earth.

We also find the concept of a bridge in Zoroastrianism and Islam. In both religions, souls have to pass over a bridge after death in order to enter their version of heaven. In Zorastrianism, the bridge is guarded by two four eyed dogs, which might have links to Wepwawet and Anubis in Egypt and Cerberus in Greece.