The story of the original fall and the Garden of Eden is an easy myth to understand once one realises that a serpent (or dragon) in a tree is a scene that has parallels elsewhere in ancient mythology. The tree has been an important mythological metaphor for the world axis in many religious traditions. The Tree of Paradise is described as growing in the middle of the Garden of Eden, suggesting it too represented the central axis of the universe,

‘In the middle of the garden he set the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.’ (Genesis 2.9)

Again, during Eve’s temptation, we read,

‘The woman answered “We may eat the fruit of any tree in the garden except for the tree in the middle of the garden”.’ (Genesis 3.2)

Elsewhere in the Bible, the book of Ezekiel links the Garden of Eden to the holy mountain and therefore the world axis,

‘You were in Eden, a garden of God…you were on God’s holy mountain…you sinned so I cast you out in disgrace from the mountain of god.’ (Ezekiel 28.13-16)

Below we see the biblical creation of man depicted on a fourth century Christian fresco. The image of the serpent wrapped round the tree is exactly the same as those we find in earlier pagan contexts.

In his letters, Paul places the Garden of Eden in the sky. He talks of a Christian (most probably himself) who ‘was caught up as far as the third heaven. And I know that this same man was caught up into the Garden of Eden [Paradise]’ (2 Corinthians 12.2-4). This must have been a Jewish tradition, as we also find Eden placed in the third heaven in a first century Jewish text called The Revelation of Moses. In that text we read,

‘The Father of all, sitting on his holy throne stretched out his hand, and took Adam and handed him over to the archangel Michael saying: “Lift him up into Paradise unto the third Heaven, and leave him there until that fearful day of my reckoning.”’ (The Revelation of Moses 37.4)

We likewise find Eden in the third heaven in a first century Jewish mystical ascent called 2 Enoch, ‘And those men took me thence, and led me up on to the third heaven…in the middle of the trees that of life, in that place whereon the Lord rests, when he goes up into Paradise [Eden].’ (2 Enoch 8.1-3)

The Garden of the Hesperides is the Greek myth most similar to that of the Garden of Eden. According to legend the Hesperides were the daughters of Atlas, and their garden was guarded by a dragon called Ladon. Below is a depiction of the Hesperides from the lower frieze of a Greek vase (420 – 410 BCE), in the centre we see the serpent Ladon entwined around the tree. Compare this to the Christian depiction above. The earliest biblical texts mentioning the Garden of Eden are Second Isaiah and Ezekiel. These date to the sixth century BCE, so are contemporaneous with Greek mythology.

Atlas probaly represented the world axis in Greek mythology, the early Christian author Clement of Alexandria (150 – 215 CE) described Atlas as ‘the unsuffering pole’ (Stromata 5.6). Hesiod wrote of Atlas, that he ‘holds the broad heaven up…in front of the clear voiced Hesperides’ (Theogony 520-2). Atlas supported the cosmic dome in the same way that the world tree Yggdrasil did in Norse mythology, or a mountain or pillar did in other traditions.

The Hesperides numbered seven in some traditions and possibly represented the Little Dipper / Ursa Minor. In the night sky this constellation is guarded by the constellation of Draco the dragon. The dragon of the Hesperides was often described as never sleeping, perhaps a reference to the fact that the circumpolar constellation Draco never sets. In his famous book on astronomy, Hyginus described the constellation Draco with,

‘This huge serpent is pointed out as lying between the two Bears. He is said to have guarded the golden apples of the Hesperides, and after Hercules killed him to have been put by Juno among the stars.’ (Astronomica 2.3)

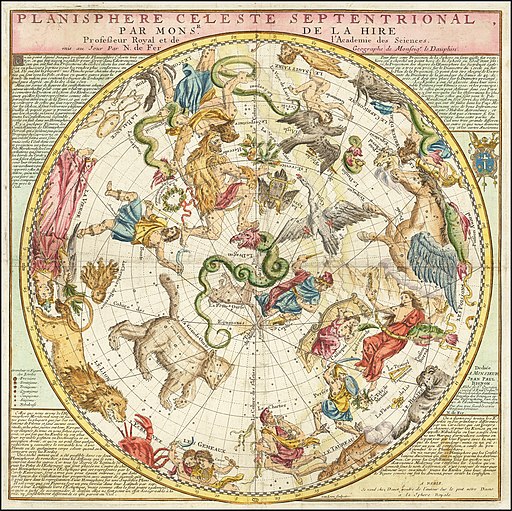

Although the tree is well known as a chief metaphor for the world axis, few have expanded the allegory to ask why a snake or dragon is often found in proximity to this tree. The answer is simple, the serpentine constellation Draco is found entwined around the axis in the night sky. Below is a sixteenth century planisphere, at the very centre of which we find Draco coiled around the pole.

The tree of the Garden of Hesperides fruited golden apples. This may be why the fruit in the Garden of Eden has often been depicted as an apple, despite there being no mention of the fruit’s variety in the Book of Genesis. The Bibliotheca is a first or second century CE compendium of Greek myths. It states of these golden apples, ‘These apples were not, as some maintain, in Libya, but rather were with Atlas among the Hyperboreans’ (Bibliotheca 2. 114).

The Hyperboreans were legendary people who lived above or beyond the north wind, linking them to the north celestial pole. They were often linked to Apollo, who was also the god worshipped at the omphalos at Delphi, the earthly end of the world axis. Aelian (175 – 235 CE) wrote, ‘The race of the Hyperboreans and the honours there paid to Apollo are sung of by poets and are celebrated by historians’ (On Animals 11.1). Strabo (64 BCE – 24 CE) mentioned an ancient garden of Apollo in Hyperborea (Geography 7. 3. 1).

Pliny the Elder (23 – 79 CE) linked the Hyperboreans to the world axis, ‘Beyond Aquilo [Boreas] there dwells, if we can believe it, a happy race of people called the Hyperboreans, who live to extreme old age and are famous for legendary marvels. Here are believed to be the hinges on which the firmament turns and the extreme revolutions of the stars’ (Natural History 4. 88). Statius (c 45 – 96 CE) wrote of ‘the Hyperborean pole’ and ‘the frosty wagoner of the Hyperborean Bear [Ursa Major]’ (Thebaid 12.650 & 1.694).

The Garden of Eden is a myth about the creation of mankind, and a belief in its fall from the heavenly realm into the earthly realm via the world axis. We find an echo of this in the Quran, which refers to the myth of the expulsion of Adam and Eve as a descent from the heavenly realm, ‘Satan deceived them—leading to their fall from the blissful state they were in, and we said, “Descend from the heavens to the earth”’ (Surah 2.36).

It’s interesting that Genesis 2.9 mentions two trees in the middle of the garden – the tree of life and the tree of knowledge. The tree of knowledge that Adam and Eve eat from may have represented the downward route of souls from heaven to earth, whereas the tree of life could have represented the upward route from earth to heaven. Christians came to associate the cross that Jesus was hung on with the tree of life, that would fit with this interpretation.

This may also be why Adam and Eve are described as being naked in Eden – souls without bodies. Hence we are told after Adam and Eve have eaten from the Tree of Life and are about to be ejected from the heavenly realm, ‘the god Yahweh made coats of skin for Adam and his wife and clothed them’ (Genesis 3.21). These garments of skin could represent the belief in souls becoming encapsulated in earthly bodies, similar to Orphism, Platonism and later Gnostic beliefs.

There’s also a possible link to Arthurian legend, the Vita Merlini tells of nine sisters living on the Isle of Avalon, of whom Morgana was leader. The name Avalon derives from the Celtic avallo, meaning apples (like in the Hesperides and Eden), and in the Vita Merlini, Avalon is called the insula pomorum (the isle of apples). Avalon’s also a land of the dead where fallen heroes live as immortals.

There may also be a link to Norse mythology. The goddess Idunn was the guardian of golden apples that maintained the gods’ youth and prevented them ageing. This is reminiscent of the concept of the Garden of Eden being an original realm where humans didn’t grow old or die.

There may be something similar in Chinese folk religion, where the gods eat the Peaches of Immortality to remain immortal. In ancient Iranian religion we have the gaokerena tree, a mythical Haoma plant that had healing properties and gave immortality to the resurrected bodies of the dead. The elixir of immortality derived from its fruit. In all these traditions we have a possible mythological representation of the belief that immortality was linked to the celestial pole and world axis.

The ancient Egyptians called the circumpolar stars ‘the imperishable stars’, there’s an obvious link that can be made between immortality and stars that never set. In the Quran, the tree of Eden is referred to as the ‘tree of immortality’ (Surah 20.120).

There may be an early version of this link in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh travels to acquire a plant that restores youth called ‘Old Man Grown Youth’. He dives enters a pool to obtain the plant, but a snake takes the plant away from him before he can possess it (The Epic of Gilgamesh XI.281-306).

We are told in the Eden myth, ‘the god Yahweh formed a man from the soil of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being’ (Genesis 2.7). This fits in with other creation mythologies from the ancient world. Man was believed to have a material body and a soul, the body being from the soil or clay, and the soul from the breath of Yahweh.

We find a similar story in Greek mythology, where Prometheus fashions man from clay or soil and Athena (the goddess of wisdom) breaths life into the clay model. In ancient Greek, the work pneuma meant both breath and spirit. Just like Yahweh, Prometheus makes humanity in the image of the gods. Ovid wrote, ‘Then man was made,…Prometheus, son of Iapetus took the new made earth, mixed it with water, fashioned it into the likeness of the gods that govern the world’ (Metamorpheses 1.84-6).

We can trace this story back to ancient Mesopotamia, where mankind was also moulded out of clay by a god or goddess (depending on the tradition). In the Atrahasis Epic, the gods sacrifice a deity called Awilu and mix his divine flesh and blood with clay to create man,

‘They slaughtered Awilu, who had the inspiration, in their [the gods’] assembly.

[The goddess] Nintu mixed clay with his flesh and blood.

That same god and man were thoroughly mixed in the clay.’ (Atrahasis Epic 224-6)

Likewise in the Gilgamesh Epic, the hero Enkidu is created from clay by the goddess Aruru (1.101-3).

Prometheus’ mythology has other parallels with the Garden of Eden. His brother Epimetheus married Pandora, who released all the evil and suffering into the world when she opened a jar she was told not to. This echoes the story of Eve in the Bible, where her disobedience supposedly led to mankind being subjected to suffering and death.