We’ve already seen how the tree is an important symbol of the world axis in many traditions, and Jesus is by no means the only religious figure to have a tree central to his passion. In a similar story to the crucifixion, the Norse god Odin hung himself from the world tree Yggdrasil, in order to discover the mystical secret of Norse runes. Just like Jesus, Odin was wounded by a lance while he hung on the tree.

The similarity of the stories of Jesus and Odin probably aided Christian expansion in northern Europe. These similarities also worried the Church, and Boniface (674 – 754 CE) cut down every tree said to be sacred to Odin. There are other links between the cross and Yggdrasil, a mediaeval German riddle book asks ‘What is the tree whose roots are in hell and whose peak is at the throne of God?’ The answer it gives is the cross. This would also be an excellent description of the world tree Yggdrasil in Norse cosmology.

We find similar mythological metaphors at play in India, where the Buddha and Jainas gained enlightenment by sitting under a tree. Early Buddhist iconography often represented the Buddha with a tree. The supposed location of Buddha’s enlightenment under the tree at Bodh Gaya is still called the navel of the earth by Buddhists today.

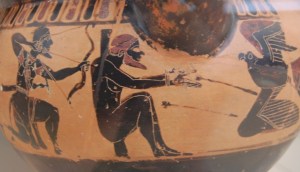

The story of the crucifixion has parallels in earlier Greek mythology. The titan Prometheus was described by Aeschylus (525 – 456 BCE) in the play Prometheus Bound as having been crucified by Zeus as punishment for bestowing the gift of fire upon men (Prometheus Bound 100-1).

Aeschylus depicted Prometheus in a manner Christians could easily apply to Jesus,

‘O universal benefactor of mankind,

Wretched Prometheus, why are you thus crucified?’ (Prometheus Bound 613-14)

ΣTAYPOΣ (stauros) is the Greek word that Aeschylus uses to describe the pole or stake to which Prometheus is bound, and it’s exactly the same word that’s translated in the New Testament as the cross upon which Jesus is crucified. Prometheus’ suffering was also represented by the Titan being nailed to a mountain, or bound to a pole or pillar. Some good examples of these from Greek literature are,

‘Here is Prometheus, the rebel: Nail him to the rock; secure him on this towering summit in shackles of unbreakable adamantine chains.’ (Prometheus Bound 5-6)

and

‘Clever Prometheus was bound by Zeus

In cruel chains, unbreakable, chained round a pillar.’ (Hesiod – Theogony 522-3)

Lucian of Samosata (c.125 – 180 CE) likewise described Prometheus’ punishment as a crucifixion,

‘We have now to select a suitable crag, free from snow, on which the chains will have a good hold, and the prisoner will hang in all publicity…

…Let him hang over this precipice, with his arms stretched across from crag to crag…altogether a sweet spot for a crucifixion. Now, Prometheus, come and be nailed up.’ (Satires p53-4)

Whether Prometheus is described as being bound on a cross, a pillar, a pole, a mountain or a rock is irrelevant, we’ve seen how they’re all commonly used metaphors for the world axis. Jehovah’s Witnesses don’t believe that Jesus was crucified on a cross, they teach that he was crucified on a wooden post, just like Prometheus.

There’s also a link to the Greek equivalent of the Tree of Eden in the story of Prometheus. He was finally freed from his punishment by Heracles, who was on his way to the visit Atlas and the Garden of the Hesperides. The mythology of Prometheus has many similarities to that of the Bible. Prometheus fashioned mankind out of earth or clay, he warned his son to build a boat to survive the deluge, he was a suffering saviour figure who helped mankind and was even crucified / bound to a stake.

Odysseus is someone else worth mentioning in relation to the crucifixion. In The Odyssey, Odysseus was bound against the mast of his ship (which is shaped like a cross), in order to hear the song of sirens without being lured to his death. The Church has often been described using the allegory of the ship, and several early Christians made a link between Jesus bound to the cross and Odysseus bound to the mast. In the fifth century Maximus of Turin wrote,

‘If, therefore, the story of this Ulysses [Odysseus] tells that his binding to the mast made him secure against all danger, how much more loudly must I proclaim that which truly came to pass! – Namely that in our own day the mast of the cross saved the whole human race from the danger of death.’ (Homilia 49)

Ambrose, an early bishop of Milan, wrote,

‘A prosperous voyage awaits those who in their ships embrace the cross as the mast they follow. They are secure and certain of salvation in the wood of the Lord. They do not suffer their vessel to stray without direction on the waters of the sea, but hurry homeward into the haven of salvation with their course set towards the fulfilment of Grace.’ (Explanatio Psalmorum 43)

Clement of Alexandria wrote,

‘Let us then shun custom. Let us shun it as some dangerous headland, or threatening Charybdis, or the Sirens of legend. Custom strangles man, it turns him away from truth. It leads him away from life, it is a snare, an abyss, a pit, a devouring evil…Sail past the song, it works only death. Only resolve, and you have vanquished destruction. Bound to the wood of the cross you will live freed from all corruption. The Word of God will be your pilot and the Holy Spirit shall bring thee to anchor in the harbours of heaven.’ (Exhortation to the Greeks 12.118)

These descriptions of Christianity as a ship, and Jesus bound to the cross of the mast guiding the boat to safe haven, seem to deliberately play on the imagery of The Odyssey.

The ideas of salvation and the safe return home of the soul could be the original concepts that underpin The Odyssey and the figure of Odysseus. A fifteenth century Italian manuscript contains a depiction of Jesus crucified on the mast of a boat that’s very similar to Greek and Roman images of Odysseus. The sirens may have represented some celestial denizens, Plato placed a siren on each of the celestial spheres in his description of the cosmos in The Republic. These sirens made the noise that was known as the harmony of the spheres.

Attis is another religious figure whose mythology has similarities with that of Jesus. Attis was a figure linked to the mysteries of Cybele / the Great Mother. He hanged himself from a tree, and was later resurrected. Every year his passion was celebrated at the same time as Easter – mid to late March.